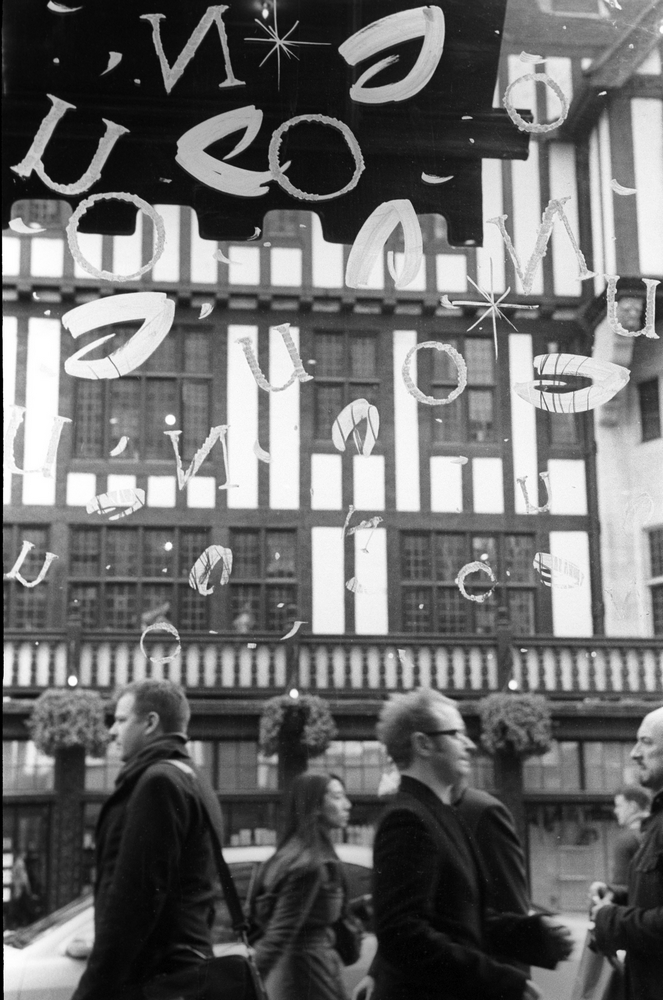

OM: Great Malborough Street is, if I may say so, a “decisive moment”; I like it because there is a sort of tension emerging from the very fact that one second earlier would have been too early, one second later would have been too late, and this tension is telling something about the fact that the crowd and the city are busy.

Johnny's bicycle is the opposite: nothing happens, everything is quiet and peaceful, it could easily have been taken half an hour before or half an hour after; I don’t know very much about this bicycle, although I have other photographs showing its owner. I like this one because the objects (bicycle and onions) are telling us the story of some men sailing from Roscoff (France) to England in order to sell their produce, they were nicknamed “Onion Johnnies”. The photograph is telling a story without showing too much.

What I have learned is that you don’t always need the tension of the decisive moment; it is good also to have some photographs which are more peaceful.

I am often trying to take the same photograph, therefore one leads to another.

The miracle with argentic photography, is that a photograph taken 20 or 30 years ago may suddenly appear on you contact sheet when you were looking for something else. With numeric photography, a lot will be lost in 20 or 30 years, just because keeping a numeric file is a big issue.

Additions:

PF: Was there a defining moment in your life as an artist?

OM: I would say 2007, when Charles Zalber called me “artist”.

PF: Where do you fit in the march of art history?

OM: I could probably be described as a humanist photographer and a street photographer, although these currants are more related to the 20th Century; perhaps it would be right to say that my work is in the same style.

PF: How do you define artists' block and have you experienced this?

OM: An artist is a very sensitive person, therefore it might happen that the artist lacks inspiration. It may happen to me, although it wouldn’t last.

PF: Where do you create?

OM: In the street, mostly in big cities.

PF: What do you hear or listen to when you create?

OM: The sounds of the city.

PF: If you have a classical studio, describe it, if you have a non-traditional studio, describe it.

OM: I don’t do the processing myself anymore, therefore I don’t have a darkroom; it takes too much time and what I like best is to take the photographs.

PF: Who gets in your way if you try to create?

OM: Nobody would ever get in my way.

PF: What was the worst thing that anyone ever said about your work?

OM: People are kind enough not to say anything unpleasant in front of me. One day I was at the book shop in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris and I saw one American lady showing two of her friends one of my postcards, it was clear they were enjoying looking at it, that is a very nice memory. I am sorry, I think I didn’t answer your question very well...

PF: What one thing would enable you to grow artistically?

OM: Mistakes; and seeing the work of other photographers, including what I like or not.

PF: Is there one other art form - like dance or music- that is like a brother to your work?

OM: Cinema perhaps, I find inspiration in a lot of old movies.

Non Art Questions:

PF: What are your living arrangement?

OM: I am lucky enough not to rely on my photographs for living; therefore I can do exactly what I want, I don’t have to sell my soul.

PF: What book are you reading now?

OM: The Anarchist’s Tool Chest by Christopher Schwarz.

PF: What's on your mouse pad?

OM: Parallel lines, it’s a cutting mat.

PF: Favorite board game?

OM: Chess.

PF: Favorite smells?

OM: Hot tar, freshly cut grass.

PF: Least favorite smells?

OM: Rotten kiwi.

PF: Favorite sound?

OM: Jazz.

PF: Worst feeling in the world?

OM: Being boring.

PF: What is the first thing you think of when you wake up in the morning?

OM: Turn off my alarm clock.

PF: Favorite color?

OM: Grey; by the way when we talk about black & white photography, there is no black and no white, there is just a large range of grey.

PF: How many rings before you answer the phone?

OM: I answer straight away, or not at all.

PF: Favorite foods?

OM: Bread, cheese and a glass of red wine.

PF: Chocolate or vanilla?

OM: No, thanks.

PF: Do you like to drive fast?

OM: Yes, but I don’t.

PF: Storms - cool or scary?

OM: Cool.

PF: What type was your first car?

OM: Citroën Ami 6, a funny car, a cross between a Ford Anglia and a Citroën 2 CV.

PF: If you could meet one person dead or alive, who would it be?

OM: Saul Leiter, I regret I didn’t have the opportunity to meet him before he died.

PF: Favorite alcoholic drink?

OM: Wine.

PF: What is your zodiac sign?

OM: Leo.

PF: Do you eat the stems of broccoli?

OM: Yes, my religion doesn’t forbid it.

PF: If you could have any job you wanted what would it be?

OM: Photographer.

PF: If you could dye your hair any color?

OM: White. I am nearly there.

PF: Is the glass half empty or half full?

OM: It is never exactly a half.

PF: Favorite movies?

OM: A Serious Man, To Have and Have not, The Man who shot Liberty Valance, Rio Bravo.

PF: What is your favorite number?

OM: 35.

PF: Favorite sport to watch?

OM: Space diving (Felix Baumgartner). It is impressive, quick, and you don’t have to watch too often.

PF: What is your greatest fear?

OM: Not to be able to answer your questions.

PF: What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

OM: If there is something I don’t like I try to change it.

PF: What is the trait you most deplore in others?

OM: I dislike people who do not care.

PF: What is your greatest extravagance?

OM: Using argentic process when numeric is so easy can probably be regarded as an extravagance. But riding a horse when it is easier to ride a motorbike is extravagant too, and I have noticed that there are people, including the police, who still ride horses in 2015.

PF: What is your favorite journey?

OM: Back home after a nice trip.

PF: What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

OM: Modesty.

PF: What do you dislike most about your appearance?

OM: Nothing. I got used to it.

PF: Which living person do you most despise?

OM: I don’t despise anybody.

PF: Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

OM: Perversion and manipulation.

PF: What or who is the greatest love of your life?

OM: My wife.

PF: Who is your favorite hero of fiction?

OM: Rick in Casablanca: he loves Ilsa so much that he lets her go away with Victor Laszlo.

PF: What do you consider your greatest achievement?

OM: Yet to come.

PF: What is your most treasured possession?

OM: Some of my films with the photographs I like best; I keep them in a safe.

PF: What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

OM: Being bored.

PF: Where would you like to live?

OM: In a log cabin right in the middle of a big city; not easy to find.

PF: Who are your favorite writers?

OM: Georges Perec, Jack London, Ionesco, Jules Verne.

PF: Who are your heroes in real life?

OM: I have been disappointed too often, I now think that heroes don’t exist in real life.

PF: How would you like to die?

OM: In good health.

PF: What is your motto?

OM: One thing at a time.

PF: What is your greatest regret?

OM: No regret.

PF: If you were to die and come back as a person or thing, what do you think it would be?

OM: I don’t think I would like to come back but if I had to, I would like to be a tree: a tree is nice and useful when alive, and when it is cut it can still be used for making paper or carpentry, even matches.

PF: Were you born an artist?

OM: No. But I believe I was born a photographer.